HANDCRAFTED, Sustainable Fashion

Currency

KHADI or KHADDAR: The Fabric of Freedom

The charm of khadi is in its artistry and in the irregularity of the yarn, which creates a unique tactile fabric. This handspun and handwoven fabric is comfortable to wear for the low twisted yarn allows the fabric to breathe and absorb moisture, and it becomes softer with every wash. This ‘fabric of freedom’ continues to spin incomes for the rural poor while reminding the country of its legacy of sustainable living and self-reliance. This remarkable fabric from the past has the potential of becoming the fabric of the future.

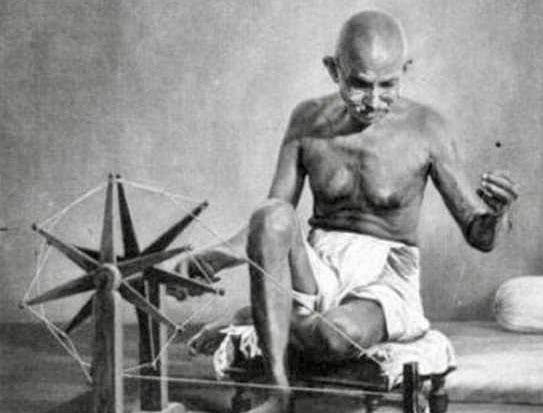

During India’s struggle for freedom from British rule, social and political activism reached new heights under the visionary leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. He saw the revival of the local village economy as the key to India’s spiritual and economic regeneration and he envisioned homespun khadi as the catalyst for India’s economic independence. Khadi became the fabric of the freedom struggle, and the charkha, the spinning wheel, the symbol of India’s Independence Movement. Rahul Ramagundam in his book, Gandhi’s Khadi, mentions that ‘Gandhi’s khadi movement, in many substantive ways, was the first social movement in modern India that brought poverty to the centre stage of Indian consciousness and made livelihood rights an issue of mass mobilisation’.

In the past, the charkha had supplemented agricultural income. It was a friend of the poor, the solace of the widow who was shunned by society, and kept the villagers from idleness. Every village had a family of weavers who wove coarse cotton fabrics without any patterns for use by the local communities. The weavers were supported by the women in the family who, in their free time, spun the yarn and created the bobbins for weaving. They had all lost their livelihood to the machine-made fabrics from Britain that were flooding the markets. The new demand for khadi provided them with regular work and rescued them from abject poverty. Gandhiji did not just revive India’s flagging handloom industry, he made the humble handspun khadi fabric the symbol of the Swadeshi Movement. Gandhiji wrote: ‘Swaraj (self-rule) without swadeshi (goods made in the country) is a lifeless corpse and if swadeshi is the soul of swaraj, khadi is the essence of swadeshi.’ Through his initiative, khadi became not only a symbol of resistance but the face of an Indian identity. ‘The message of the spinning wheel was much wider than its circumference.’

Rahul Ramagundam mentions that ‘Gandhiji’s ingenuity was in linking khadi, a process and a commodity, with politics. It was not as if he invented khadi. It was always there, woven by the local communities in every village. His contribution was not in revival, but to make it into a tool for a constructive programme of creating dignified livelihoods, self-sufficiency and much more. The charkha became the symbol of non-violence and economic self-sufficiency’.